Over Optimism of Rewrites in Software Engineering

Dev Leader Weekly 126

TL; DR:

Software rewrites are almost ALWAYS underestimated

The “all or nothing” approach is the most dangerous trap

The Strangler Fig pattern lets you rewrite incrementally and safely

Join me for the live stream (or watch the recording) on Monday, February 9th at 7:00 PM Pacific!

Why Do Software Rewrites ALWAYS Take Longer Than Expected?

I saw a post on the ExperiencedDevs subreddit that really resonated with me. Someone pointed out that after about 8 years in the industry, every single rewrite they’ve seen has taken significantly longer than teams planned for. And for some reason, people always act surprised.

Spoiler alert: that’s also been my experience.

And I’m not talking about being a little bit off. I’m talking about -- if someone tells me “it’s going to take us X amount of time to rewrite this,” I would at least double it. If they say a year, I’m saying two years. At least. That’s just based on my own lived experience with various rewrites across my career.

Now, my goal here isn’t to say “a rewrite is the devil, never do it, never consider it.” It’s just that I think a lot of the time, rewrites are approached as this silver bullet solution for all the problems we have -- and the amount of time and complexity to pull it off gets grossly underestimated. You can check out my full thoughts on this in the video below:

Why Teams Push for Rewrites

So what motivates a rewrite in the first place? In my experience, it’s usually the engineering team that’s driving it -- not the business. And I think one of the big reasons is knowledge dispersion.

When you have these really large or complex systems, no single person knows everything about the system. As systems grow and scale and age, people on teams change. The knowledge about the system becomes inconsistent -- there are gaps. Some people know some parts, no one knows everything, and certainly everyone doesn’t know everything.

When you have that kind of disparate knowledge, it becomes easy to rally behind the idea of: “Well, if we just start from something we all agree on, we can make this better.” You know there’s a problem. There’s that big god class that’s super legacy and brittle and no one seems to be able to touch it. And so the thinking is: we can solve this. We can be the ones that make it better. We’ll also fix this problem of legacy code that no one really understands.

And look -- it’s hard to argue with that on the surface. It seems logical. Given the severity or complexity of some structural issues in a codebase, I can certainly see why people would be motivated to do that. I’ve literally been part of conversations where I’ve felt motivated to say, “Man, if we just didn’t have this thing here, we could do this so much better.”

The Two Clean Slates Problem

But here’s where things start to fall apart.

When people say “rewrite,” it usually means everything. Starting from scratch. You get this green field from an engineering perspective to go do all the right things -- get it right this time.

The danger from the business side? When you have systems or products that have been around for a long time, there are a lot of features and functionality that exist. Hidden menus that you never thought about. Some users that absolutely depend on those menus, buttons, or workflows. There’s all this knowledge and history that went into getting those flows together.

So what happens is you end up with two clean slates:

A clean slate from a code and architecture perspective

A clean slate from a feature parity perspective

Engineers focus on how they’re going to solve all the problems technically -- the architecture, the infrastructure. So much attention goes there. But there’s not enough conversation around parity -- what needs to happen in terms of usability, migration strategies, and communicating changes to users. And I feel like that’s a huge miss almost all the time.

The Resource Split

Beyond that, we’re dividing resources. If you have a legacy system that’s running that users are paying for, and you start a rewrite, you have to split resources somehow.

You could move everyone to the new thing to get it done as fast as possible. But while that’s happening, you have paying users who may have issues, who may be hoping for feature updates on a cadence they’ve come to know and love -- and that’s not getting attention.

Or you keep some people back on the legacy system. Now you’ve got the overhead of managing two groups focused on different roadmaps, different priorities, and you’re not prioritizing the rewrite as much, so it’s going to take longer.

There’s a spectrum of how you split resources -- people and time. I’m not saying there’s one right answer. I’m just saying this is a huge factor in complexity that also gets grossly underestimated.

The Scary Trap

The scariest trap I see with this stuff? Say you go all in on a rewrite. There’s excitement in the beginning because everything’s new. Tons of momentum early on because things are being stood up. Then a bit of a lull. Then things come together and you start getting more momentum again.

But as time elapses, you start realizing: “Hey, I know we said we’d build the architecture perfectly this time, but as complexity gets added with new feature sets... oh, we didn’t factor this part in.” So the architecture has to change a little bit. And it keeps happening. Now your pristine architecture is starting to get some cracks in it.

And then people in product start looking at what’s being produced and going, “Wait, we didn’t account for this feature. There’s a gap here.” One more thing to add back in. And another. And another. The timeline keeps moving out.

And then you hit this point -- maybe multiple points -- where people are questioning: should we keep going?

That is the worst scenario to be in. You’ve made this conscious decision to go all in on something, and now you’re like, “What the hell are we going to do here?” This isn’t panning out to be perfect sunshine and rainbows. Because -- and this is the thing -- it’s software development. It’s never going to be perfect sunshine and rainbows.

To this person’s point in the Reddit post: why are we always surprised? You’re trying to rewrite something from scratch that took years to build. Software systems that took 3, 5, 10 years. We can’t even estimate feature deliveries in the order of days or weeks, and you’ve got a timeline for a full rewrite that you feel confident in? It’s completely crazy to think we’re going to get that right. Doesn’t mean it can’t be successful -- but it’s crazy to think there won’t be surprises.

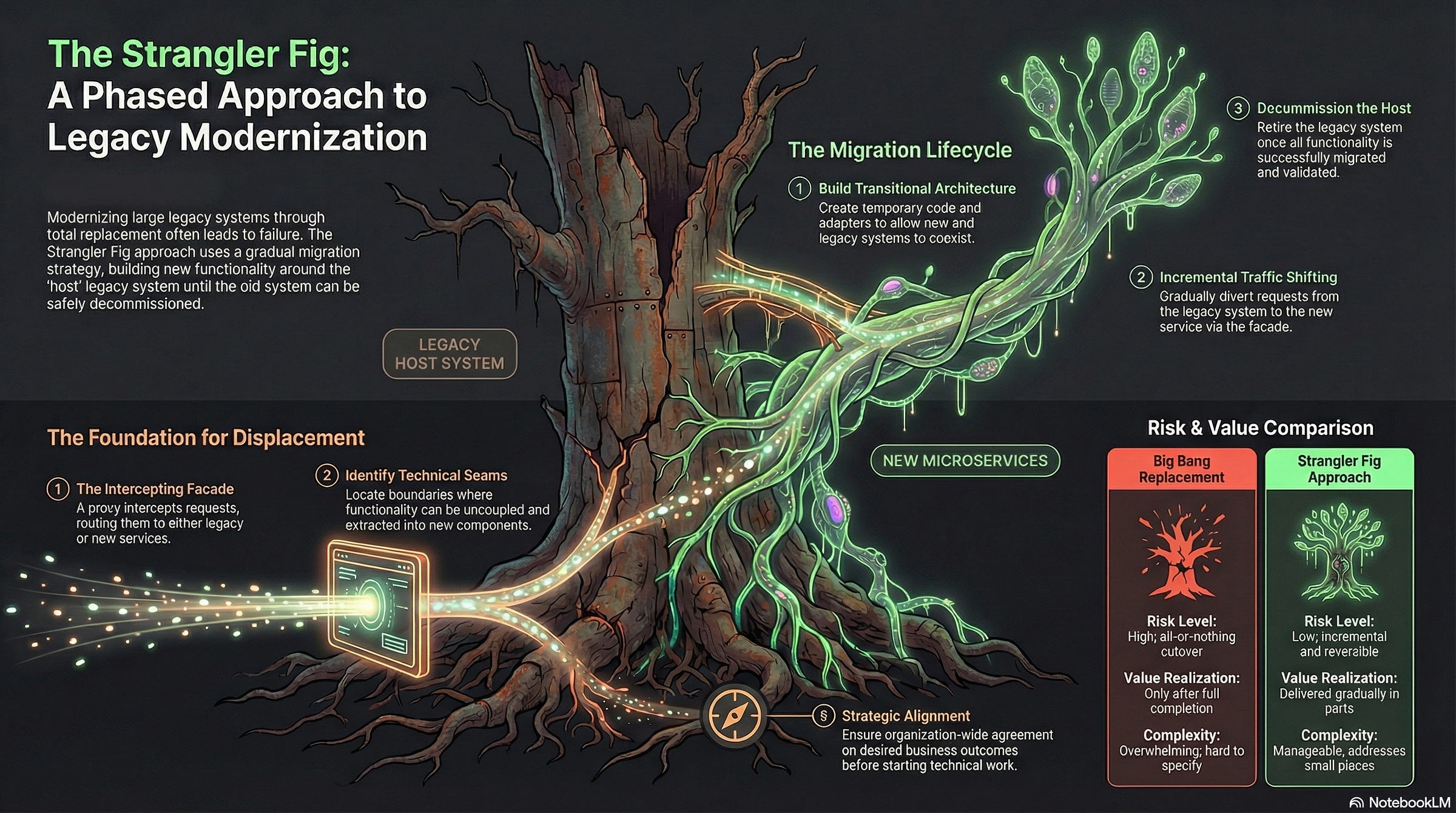

The Strangler Fig: A Better Way

So how are we doing this instead? Martin Fowler coined this term called the Strangler Fig a long time ago. He wrote about it in his Strangler Fig Application article, and the naming comes from these types of vines he saw in the rain forests of Queensland. These vines germinate in a nook of a tree, draw nutrients from it as they grow, and eventually become self-sustaining -- sometimes the original host tree dies and the fig remains as an echo of its shape. Martin saw this as a striking analogy for how we can modernize legacy software systems.

And here’s the thing that really stuck with me from his article: he points out that trying to do a simple replacement -- “we know what the old system does, so just build a new one that does exactly the same” -- goes down in flames most of the time. The alternative he and his colleagues prefer is a gradual process of modernization. Like the fig, it begins with small additions, often new features, built on top of yet separate from the legacy codebase. As you do this, you move bits of behavior from the legacy system into the new code.

The idea when it comes to rewrites is: instead of taking your entire product or service and going “we’re starting from zero,” you do it in pieces. You find ways to segment how you can start rewriting things. You build up the new pieces, and then you slowly start taking code paths and pointing them to the new parts. You start replacing parts of your system this way.

Instead of it being a full-on rewrite where you do an all-or-nothing thing, you incrementally rewrite chunks of the software.

How It Works in Practice

Take a set of microservices that all work together. Maybe a single microservice is the granularity of rewrite you go address. You stand up the new service, start sending some traffic to it proportionally, get it tested, get it working. Once you’re confident, you cut over all the traffic and cut out the old one. You didn’t rearchitect your entire system from scratch -- you picked one service.

If it’s not microservices and it’s modules in an application -- same concept, just a different transport. How can you start rewriting a module and cutting things over to it?

But How Do You Actually Break It Up?

This is where people often push back: “Okay, great concept, but how do I actually figure out where to slice?” Ian Cartwright, Rob Horn, and James Lewis wrote an excellent set of Patterns of Legacy Displacement on Martin Fowler’s site that digs into exactly this. They lay out four high-level activities:

Understand the outcomes you want to achieve -- Get alignment on what you’re actually trying to accomplish. Is it reducing cost of change? Improving business processes? Retiring old infrastructure?

Decide how to break the problem into smaller parts -- Find the seams in your current business and technical architecture. How does your big monolithic solution map to different business capabilities? Can you extract individual needs for independent delivery?

Successfully deliver the parts -- Use strategies like canary releases, event interception, or diverting flow to cut over from the legacy system incrementally.

Change the organization -- This one is huge. Legacy systems become rigid and brittle because the design thinking and organizational processes that produced them built them that way. If there’s no change in organizational culture, the new systems will end up in a similar mess.

One thing from that article that really hit home for me is their observation that technology is at most only 50% of the legacy problem. Ways of working, organization structure, and leadership are just as important to success. That lines up perfectly with what I’ve seen -- teams that only focus on the tech side of a rewrite and ignore the organizational side tend to end up right back where they started.

They also call out something I’ve lived through multiple times: the Legacy Replacement Treadmill. Organizations go through these 3-5 year modernization programs, and at some point during each one, changing business needs overtake their current tech strategy and trigger the need to start over. If they took a “big bang” approach, that means abandoning most of the work. Sound familiar?

The key insight is that you need to be able to build transitional architecture -- code that lets the new and legacy systems coexist, even though that code will eventually go away. People often balk at this because it feels like waste. But the reduced risk and earlier value from the gradual approach outweigh its costs.

Why I Like This

Is there overhead to developing this way? Yes. But that overhead affords you flexibility. If we can minimize the amount of overhead and still maximize the flexibility we get from it, that’s still aligned with my best interest in software development.

Think about it like waterfall versus agile. The idea with agile is having tighter feedback loops to make sure we keep steering in the right direction. The strangler fig approach gives you more opportunity for feedback. Yes, there could be more overhead, but instead of going completely off-course or misunderstanding your estimates, you do it in smaller chunks, get feedback, and adjust.

Real Examples from My Career

I’ll give you two examples from my professional experience.

The Desktop Product: We had a SQLite database with a schema that was becoming really limiting. The amount of data had grown orders of magnitude, and our schema made working with that data a nightmare for new features. We started doing this data layer where we could share things in a new format -- kind of like the strangler fig approach for our data layer. But then we also just rewrote the entire product from scratch. We lived the problem: “Oh, users actually use this other thing this particular way and we didn’t think about that.” It was a nightmare. It was successful in the end, but I would do it completely differently if I had to do it again. I would absolutely try to build out modules and move things over to the new pattern over time.

The Service: We had a legacy service where making code changes was quite difficult, and performance was being squeezed to the max. A new service was introduced primarily to address performance constraints. As the new service was built up, scenarios were brought over incrementally. Traffic was directed to the new service, tested, validated. Then the next scenario, and the next one. Over time, all the legacy code paths went from being 100% called down to zero, until you could turn off the old one.

Both of these were successful rewrites. But even the one done incrementally was probably underestimated for how long it would take. The first one? Certainly underestimated.

The Takeaway

Trust that when people are talking about rewrites and estimating the scope, it’s going to be way off. Whatever you say with as much confidence as you have, double it. It’s going to be off if you’re doing a full rewrite.

But what I’d encourage you to do is figure out how to step back from an all-or-nothing approach and see how you can do it incrementally. You might find that you get far enough along and realize -- hey, maybe parts you wanted to rewrite? No one even uses them. Maybe you deprecate them instead of rewriting them. You will learn things as you go, and approaching it incrementally gives you the opportunity to do that.

There is overhead to doing things incrementally. But that overhead affords you the flexibility to avoid cutting off life support for something that’s literally the reason users pay or the reason your entire platform exists.

Incrementally is the way I recommend, if you can.

Join me and other software engineers in the private Discord community!

Remember to check out my courses, including this awesome discounted bundle for C# developers:

As always, thanks so much for your support! I hope you enjoyed this issue, and I’ll see you next week.

Nick “Dev Leader” Cosentino

social@devleader.ca

Socials:

– Blog

– Dev Leader YouTube

– Follow on LinkedIn

– Dev Leader Instagram

P.S. If you enjoyed this newsletter, consider sharing it with your fellow developers!